Jacques Sapir, Contributing Editor, FSU

The year 2009 was a tremendous shock for the hydrocarbon-producing sector in Russia, as it was for the whole Russian economy. However, looking back from the end of 2010, the sharp downturn in oil prices induced by the world financial crisis has had a mixed impact on the Russian oil and gas sector. Crude oil prices fell from a historic record high of $147/bbl in July 2008 to below $50 in November 2008. Nonetheless, by year-end they were rebounding, and by the end of 2010 they were back to over $88/bbl.

The decline of demand in Russia’s key export markets in the former Soviet Union and Europe reduced the profits of Russia’s vertically integrated oil and gas companies (VIOCs), and as a result they made cuts in investment programs and capital expenditures. The financial and economic crisis also limited access to international capital markets, the main source of financing for Russian companies. Ultimately, many questions remain, such as changes in energy policy of EU countries and their actual demand for Russian gas, the possibility of diversifying Russian export markets (LNG exports to the Asia-Pacific region), and the eventual level of profitability of some recently announced projects.

However, the crisis didn’t prevent the VIOCs from increasing oil production by 1.2% in 2009, reversing a three-year decline, and it did not prevent the major oil and gas producers from continuing their outward expansion.

RESERVES AND DRILLING

According to BP statistical data, Russia leads the world with 44.38 Tcm (1,567 Tcf) of proved natural gas reserves (about a quarter of the world’s total) and 74.2 billion bbl of proved oil reserves.

The global crisis and the decrease in oil and gas prices led to a worldwide decrease in revenues and a drop in exploration activities. However, according to Russia’s Central Dispatching Department of Fuel Energy Complex (CDU TEK), total drilling activity in Russia declined by only 5.8% in 2009, less than the world average. Exploration drilling declined in 2009 by 45.5% compared to 2008. Nevertheless, some 74 gas and oil fields were discovered in 2009 (compared to 66 in 2008), including 41 fields in the Volga-Ural oil province, 20 in Western Siberia, seven in Eastern Siberia, five in the Timan-Pechora oil province and one in the Caspian Sea.

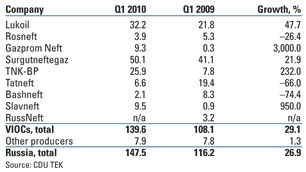

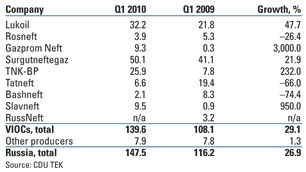

This trend was typical of Russian oil and gas companies, but Surgutneftegaz, which accounts for 39% of total exploration drilling, saw an 8% average increase. A slight acceleration in exploration drilling in the first quarter of 2010 is a positive sign, but 2010 year-end results will probably not compensate for the previous year’s decline, Table 1.

| TABLE 1. Exploration drilling, Q1 2009 and Q1 2010, thousand meters |

|

In February 2010, Russian agency Rosnedra forecast a decline in reserves replacement to 86% of 2009 levels due to declining state funding of geological activities. In defiance of this gloomy prediction, 2010 has been marked by Rosneft’s discovery of a new strategic oil field, Sevastianovo, with 160.2 million tonnes of C1 + C2 (roughly analogous to proved plus probable) reserves in the Irkutsk region of Eastern Siberia. By the same token, the fact that Russia and Norway finally reached an agreement in April 2010 on delimitation of the Barents Sea and part of the Arctic Ocean opens new opportunities for oil and gas exploration and development activities in the far north.

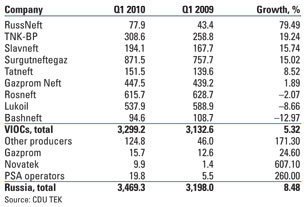

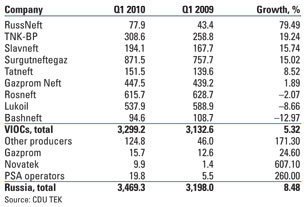

Production drilling, which accounts for about 90% of total drilling, was largely maintained in 2009, registering only a 3.5% decline. Results of the first quarter of 2010 are also quite positive. The leading VIOCs increased production drilling by 5.3%, while the average increase for the entire sector was 8.5%, Table 2.

| TABLE 2. Production drilling, Q1 2009 and Q1 2010, thousand meters |

|

Gazprom’s production drilling, though showing an increase, is lower than Novatek’s (its major counterpart in the interior market), indicating that consequences of the global crisis continue to hamper performance for the world’s biggest natural gas producer.

OIL PRODUCTION

Despite an unfavorable global environment and pressure from OPEC to restrain oil production during the economic crisis, in 2009 oil and gas condensate production in Russia reached 494.2 million tonnes, a 1.2% increase after a five-year decline, Fig. 1.

|

|

Fig. 1. Russian oil and gas condensate production and year-over-year production growth, 2000–2010.

|

|

Year-end results by major VIOCs are quite diverse. Some increased production in 2009, such as Rosneft (with 2.7 million tonnes more than in 2008, a 2.5% increase), Lukoil (2.1% increase) and TNK-BP (2.2% increase). Others, like Surgutneftegaz and Gazprom Neft, cut their production (3.3% and 1.6%, respectively).

Nevertheless, positive trends in the oil industry continued in 2010, Fig. 2. One of the most important achievements has been the start of offshore oil extraction in the Russian Caspian. In April 2010 Lukoil put onstream Yury Korchagin field, with recoverable reserves estimated at 211 million bbl of oil and 63.3 Bcm of natural gas. In October 2010, Russian oil output reached a new record level of 10.26 million bpd, beating the high of 10.16 million bpd in September and exceeding Saudi Arabia (which was limited by OPEC quotas). Results for January through October showed a 2.4% increase in oil production (420.2 million tonnes) compared to the same period in 2009. This is largely attributed to the startup in September of Odoptu Field development (with oil reserves estimated at 20 million tonnes), the ExxonMobil-led Sakhalin-1 project, working under a production-sharing agreement, and further development by Rosneft of Vankor Field (520 million tonnes of reserves), which has continued to contribute to the company’s output. Rosneft registered an 8.8% increase in the second quarter of 2010 versus the same period in 2009, and 1.2% in second- quarter 2010 versus first-quarter 2010.

|

|

Fig. 2. Oil and gas condensate production by month in 2010 and growth compared with the same month in 2009.

|

|

According to the Russian Ministry of Economic Development, oil and gas condensate production in 2010 is estimated at 499 million tonnes, an increase of 1.1% over 2009. Currently, Russia’s Ministry of Energy maintains its projection for oil output to reach 500–505 million tonnes/year by 2020 and 530–535 million tonnes/year by 2030, the level set in the national energy strategy adopted in November 2009 (ES-2030).

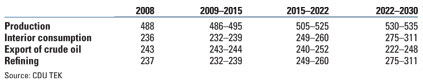

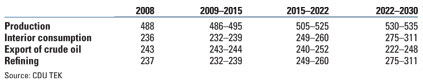

According to ES-2030, oil production will grow by about 9% by 2030 compared to 2008, and refining is expected to increase by 16–31%, Table 3. A strong emphasis is put on the geographical diversification of Russia’s energy resources, with more active roles to be played by the country’s eastern regions—Eastern Siberia, with production growth from 0.5 million tonnes in 2008 to 75–69 million tonnes in 2020–2030, and the Far East with production growth from 13.8 million tonnes/year in 2008 to 32–33 million tonnes/year in 2022–2030.

| TABLE 3. Forecast of oil industry dynamics to 2030, million tonnes |

|

Exports of crude oil and oil products are expected to decrease by 6.4%. The share of exports to the EU countries (but not necessarily delivered volumes) will be gradually reduced, accompanied by a gradual increase in the share going to the Asia-Pacific countries, up to 22–25% compared to 8% in 2008. This shift could be representative of a long-term trend.

GAS PRODUCTION

In the short term, the Russian gas industry suffered much more from the crisis than did the oil industry, Fig. 3. However, here again, the global financial and economic crisis has had a mixed impact. The year 2009 witnessed a sharp decline of global industrial output, which affected global energy consumption and hence gas demand. Russian gas production declined by 14.4% from 665 Bcm in 2008 to 582 Bcm in 2009.

|

|

Fig. 3. Russian gas production and Gazprom percentage of total, 2000–2009.

|

|

The 16% drop in Gazprom’s gas production (to 462,160 Bcm) in 2009 is largely attributed to demand decreases in FSU and EU countries, and also to the expansion of the LNG spot market at lower prices. Gazprom, which has always benefited from long-term take-or-pay contracts linked to oil prices, was obliged to renegotiate its contract terms with Italy’s Eni and Germany’s Ruhrgas. Due to the financial crisis and the development of shale gas in the US, the Shtokman Field development (C1 + C2 reserves accounting for 3.8 Tcm of gas and about 37 million tonnes of gas condensate) has been postponed from 2013 (pipeline construction) and 2014 (LNG production) to 2016. Besides its importance for Russia’s gas exports and market diversification, this project is also part of the Gazprom’s gasification plan in the Mourmansk region.

In 2010, gas production has been recovering slightly, supported by increased industrial output inside Russia, as well as demand increase for Gazprom’s gas in Europe, Fig. 4.

|

|

Fig. 4. Russian total production and Gazprom production by month in 2010, and comparison of total with the same month in 2009.

|

|

The Russian gas sector is actually much more concentrated than the oil sector because of Gazprom’s monopoly on the gas transport system. By 2009, the company’s production accounted for 79.2% of total Russian gas output (461.5 Bcm out of 582.4 Bcm). However, this share has been decreasing and independent gas producers have been slowly gaining ground. Novatek, Russia’s largest independent gas producer, had output 14 times less than Gazprom’s in 2009 (32.8 Bcm compared to 461.5 Bcm). But in November of that year, the company succeeded in gaining on Gazprom’s market share by making a deal to supply Russia’s power trader Inter RAO and its regional generation company OGK-1 with around 65 Bcm/year of gas beginning in 2010 and extending through 2015.

In recent years, the oil companies’ share in total gas production has been increasing. Russian VIOCs Rosneft (12.68 Bcm), Lukoil (10.2 Bcm), TNK-BP and Surgutneftegaz (13.6 Bcm) currently account for about 80% of gas produced by Russian oil companies. However, the absence of a competitive energy market due to Gazprom’s monopoly greatly limits gas production outside the group, despite an official policy of fostering competition, recognized since 2003. It is also contradictory to the energy efficiency program initiated in January 2009 by the Russian government for oil companies to limit associated petroleum gas levels in flares to no more than 5% of the volume of produced associated gas, beginning in 2012.

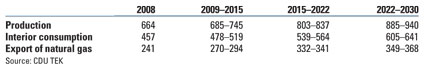

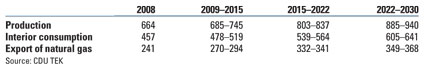

According to ES-2030, gas production will increase 33–42% to reach 885–940 Bcm by 2030, Table 4. The main production centers will gradually shift from Western Siberia to the Far East, Eastern Siberia, Yamal and the Arctic shelf.

| TABLE 4. Forecast of gas industry dynamics to 2030, Bcm |

|

Gas exports are forecast to reach the level of 349–368 Bcm, of which Asia-Pacific countries will account for 20%. However, Europe will remain the principal consumer of Russian gas for the foreseeable future.

In this respect, the transit capacity for both oil and gas will be improved by the upcoming Nord Stream project (with a capacity of 55 Bcm/year) and the signing of a formal agreement for the South Stream project.

GOVERNMENT POLICY

Although, according to the Ministry of Finance, the percentage of oil and gas revenues in the Russian gross domestic product declined slightly in 2009 (7.6%, compared to 10.5% in 2008) as did their contribution to federal budget revenues (40.7% in 2009, down from 47.3% in 2008), the Russian economy will remain heavily dependent on hydrocarbon exports for the foreseeable future. The energy sector is a major concern for the Russian government, considering its economic, political and geostrategic importance, but sometimes national economic and geostrategic interests conflict with those of the energy companies.

The post-crisis period of 2009–2010 has been marked by a large number of state initiatives in the energy sector. In November 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, in his annual state-of-the-nation address, called for the modernization of the economy aimed at reducing Russia’s dependence on raw materials, and for the development of an economic model based on innovation and energy efficiency. This address was followed by the adoption of the new energy strategy to 2030. Its key objectives are an increase of energy efficiency (power efficiency, energy savings and associated gas utilization), new oil and gas field development in eastern regions (Eastern Siberia and the Far East) and in the High North (Arctic shelf), and export diversification to the Asia-Pacific market (China, Korea, Japan and India).

The balance between external growth—both outward expansion and foreign asset acquisition—and the development of investment-consuming projects inside Russia is not easy to find. Contrary to what had been expected, the recent financial crisis did not prevent Russian VIOCs from continuing their deliberate global strategy. In the field of E&P activities, a consortium will exploit the Junin 6 Block in the Orinoco heavy oil belt of Venezuela, a project that will have a capacity of 200,000 bpd. The consortium, including Lukoil, TNK-BP, Rosneft and Gazprom, will operate in cooperation with Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) under an exploration license obtained this year.

The financial and economic crisis created opportunities for Lukoil, which continued to acquire stakes in refineries and retail marketing networks in Europe. In June 2009, the company acquired Dow Chemicals’ 45% stake in Total Raffinaderij Nederland (TRN) for $725 million.

Reform of natural gas prices has been a concern for years. The Russian government recognizes the need to move domestic natural gas prices toward parity with export sales (while being careful not to interfere with Gazprom’s monopoly). But, being a politically sensitive issue because of its social impact on the population, the schedule of this reform remained uncertain for a long time. In April 2010, Gazprom negotiated with the government a new price formula for domestic industrial consumers starting in 2011. The price reform will make Gazprom’s sales in the domestic market more profitable. Currently, 70% of its production is for the domestic market, but 82% of the group’s revenues come from exports.

The government is also preparing fiscal reform on export duties, and a new profit-based tax regime on new oil fields will be introduced in 2012. To compensate for lower taxation on new fields, export duties on oil products will be raised from the current 55% to 85–90%.

Another initiative that is under consideration by the government concerns the mineral extraction tax rate. According to Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, the planned 61% rate increase for the gas sector will provide more than 50 billion rubles per year of additional revenues to the federal budget. In the oil sector, the extraction tax was reduced by 45.8% in dollar terms in 2009, due to lower oil prices and steps taken by the Russian government in 2008 to lower the tax rate. According to the ministry, the return of fiscal charges starting in 2012 is justified by the world economic recovery, increased demand and higher oil prices. In a sense, the energy sector is a victim of its close ties with Russia’s national interests to promote the economic growth.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the pattern we have seen for years will continue largely untouched by the crisis. The Russian government will allow Russian companies to “go global” and to raise huge amounts of money from Western financial markets, but it is keeping a close hand both on the social consequences of internal prices and on taxes. Internal exploration and production will be increased, but within limits. The main change brought on by the crisis is the reduced importance of Europe and the growth of Asia as markets for Russian hydrocarbons. However, infrastructure inertia exerts a considerable drag on the pace of this change. The Asia share of exports will grow, but slowly.

|

THE AUTHORS

|

| Jacques Sapir is professor of economics at EHESS-Paris and at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. He is a regular contributor to World Oil. |

|