PRAMOD KULKARNI, Editor

|

|

From left: The first permit for deepwater drilling after last year’s moratorium was issued with the Helix Producer as the option for spill containment. Interior Secretary Ken Salazar examined the interim MWCC containment system in late February. The US government issued a permit in mid-March to Petrobras for use of the FPSO BW Pioneer to produce from Cascade and Chinook fields, a first for the Gulf of Mexico.

|

|

The Gulf of Mexico has been labeled “the Dead Sea” several times in its recent life. The first pronouncement came in 1973 when a series of 10 big-budget offshore wells came up dry. Persistent wildcat drilling led to both the discovery of major fields in shallow waters and the opening up of the deepwater areas over the next three decades. The second obituary was written in 2005 after three years of steady production declines. In September 2006, Chevron discovered the massive Jack field and the industry embarked on a new era of exploration in the ultra-deepwater Lower Tertiary play. McMoRan’s discovery of the giant Davy Jones field in January 2010 in only 20 ft of water showed that there was plenty of life left in the world’s first offshore oilfield sector.

Then suddenly on April 26, all drilling activity came to a grinding halt after the tragic sinking of the Deepwater Horizon and the Macondo well blowout. The Obama administration imposed a six-month moratorium as crude oil inundated the Louisiana Gulf Coast. The moratorium ended in October after much of the coastline had been cleaned up and claims had been paid to many of the victims. A newly organized Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and Regulatory Enforcement (BOEMRE) began issuing permits for shallow-water drilling under a much stricter safety and spill containment regime, but only issued the first deepwater permit on Feb. 28 after a “permitorium” of almost six months. How quickly additional permits are issued may depend on how soon the BOEMRE staffs up to handle the exponential increase in permit review paperwork as well as how the agency responds to political pressure from the lobbying initiatives of industry organizations such as the American Petroleum Institute, the Independent Petroleum Association of America, the Petroleum Equipment Suppliers Association and the recently formed Shallow Water Coalition, as well as the new Republican majority in the US House of Representatives.

Here’s an overview of the sea change that has taken place in the Gulf of Mexico in just one year and the prospects for exploratory drilling and production as additional permits are issued.

MACONDO WELL BLOWOUT AFTERMATH

April 20 will be the first anniversary of the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon semisubmersible and the resulting Macondo well blowout. The incident caused the deaths of 11 rig workers and the spilling of 4.9 million bbl of oil an initial rate of 62,000 bpd, which declined to 53,000 bpd by the time the well was capped on July 15, according to the Flowrate Technical Group, consisting of scientists from the US Geological Survey and the Department of Energy. Through the combined efforts of BP, the US Coast Guard and an army of volunteers, about 17% of the oil was recovered from the wellhead, 5% burned at the surface, 3% skimmed from the surface, 8% chemically dispersed, 16% naturally dispersed and 25% evaporated or dissolved, according to scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA). About 26% of the oil remains, possibly on the ocean floor. BP has paid about $11.2 billion in claims out of a $20 billion escrow fund. In addition, the company has distributed $100 million as a fund for unemployed rig workers and plans to spend an additional $500 million on a Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative to study the potential effects of the Macondo spill on the environment and public health.

The Macondo blowout has been subject of US congressional hearings and investigations by at least five government agencies, including the Coast Guard and President Barack Obama’s National Oil Spill Commission. The commission’s final report concluded: “The explosive loss of the Macondo well could have been prevented. … The immediate causes of the Macondo well blowout can be traced to a series of identifiable mistakes made by BP, Halliburton, and Transocean that reveal such systematic failures in risk management that they place in doubt the safety culture of the entire industry.”

A forensic report on the failed Macondo blowout preventer (BOP) was issued by BOEMRE’s contractor Det Norske Veritas on March 23. The report concluded that the “primary cause of failure was identified as the [blind shear rams] failing to close completely and seal the well due to a portion of drill pipe becoming trapped between the ram blocks.” According to DNV, other contributing causes included the blind shear rams’ inability to move the entire pipe cross-section into the shearing surfaces of the blades. As a result, the flow of well fluids was uncontrolled downhole of the upper variable bore rams.

The final apportionment of blame will depend upon the outcome of the US Department of Justice’s lawsuit against BP and eight other companies as well as numerous other individual and class action lawsuits and possible criminal proceedings.

MMS TO BOEMRE

The Macondo blowout dealt a death blow to the Minerals Management Service (MMS), which was responsible for both Gulf of Mexico lease sales, regulatory enforcement and royalties. Consequently, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar reorganized the agency into BOEMRE, which in turn was intended to be reorganized into three separate agencies to handle leasing and environmental and resource analysis (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management); permitting and safety enforcement (Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement); and revenue assessment and collection (Office of Natural Resources Revenue). The latter has already become a separate entity within the Office of the Secretary, but prying apart the other two functions of BOEMRE remains a work in progress.

The administration is seeking to double BOEMRE’s annual budget to $358.4 million in fiscal 2012 to hire additional staff and allow the agency to conduct detailed engineering reviews of offshore drilling and production safety systems and to develop new risk-based inspection criteria and safety oversight strategies, including real-time monitoring of key drilling activities. The agency seeks to offset this added cost by charging the oil and gas operators $65 million in additional inspection fees.

DRILLING SAFETY MANDATES

The drilling safety reforms imposed by BOEMRE under its first director, Michael Bromwich, include:

• Notice to Lessees (NTL) 06, which requires exploration plans to deal with a potential blowout and planning for the worst-case discharge scenario

• Drilling Safety Rule, which imposes new standards for well design, casing and cementing, and requires certification of these plans by a certified professional engineer

• Workplace Safety Rule, which imposes performance-based standards for drilling and production, including for equipment, safety practices, environmental safeguards and management oversight

• NTL-10, which requires a corporate compliance statement and information about subsea blowout containment resources

• “Idle iron” NTL, which requires operators to set permanent plugs for about 3,500 nonproducing wells and dismantle about 650 production platforms that are no longer in use.

The BOEMRE regulatory mandates have created additional work for engineering service companies that can serve as certified verification agents (CVAs). For instance, MCS Kenny performed as the CVA for the free-standing hybrid risers (FSHRs) that Petrobras is using for the deepwater Cascade/Chinook project in the Walker Ridge area of the Gulf. The FSHR system is the first engineering project to be subjected to BOEMRE’s CVA process, which requires review and verification of all stages of design, fabrication and installation. Many challenges encountered and overcome during the CVA process for Petrobras will set precedents for future FSHR projects in the Gulf, said Ayman Eltaher, technology and R&D manager for MCS Kenny.

Industry reactions. In the aftermath of the Macondo blowout, BP has implemented stricter internal testing standards and procedures for well operations, including BOP testing, evaluation of cement integrity and rig audits. The company is building a new capping stack based on lessons learned from the effort to cap the Macondo well. Additionally, BP is instituting a company policy to not drill a well using a dynamically positioned rig unless equipment and procedures are in place for shutting in the well and drilling a relief well.

|

|

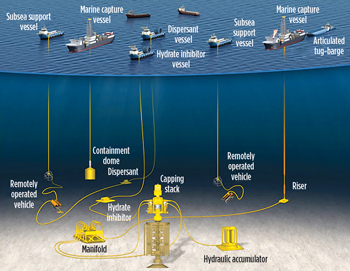

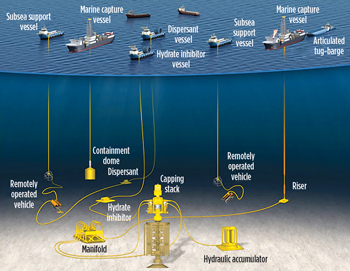

Fig. 1. The MWCC interim containment system.

|

|

|

|

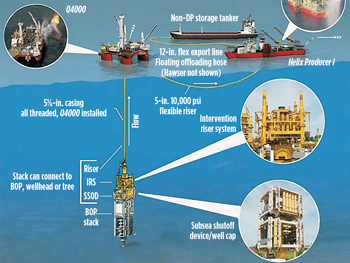

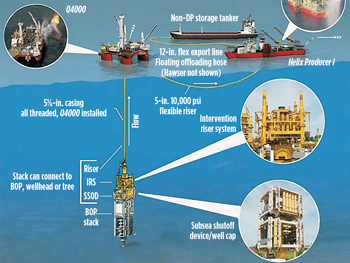

Fig. 2. The Helix Fast Response System.

|

|

Several Gulf of Mexico operators, including ExxonMobil, have sought to distance themselves from BP’s problems. ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson suggested before a congressional hearing in June that ensuring safety is a question of risk management, implying that his company would have done a better job. Similar sentiments were expressed by operators in the North Sea, where safety standards were strengthened in the aftermath of the 1988 Piper Alpha blowout.

Political undercurrents. Political reactions to the oil spill have been split along a polarized chasm of progressive Democrat versus conservative Republican ideologies. A new Republican majority in the US House of Representatives is in favor of a rapid return of oil and gas activity in the Gulf of Mexico, whereas the Democratic establishment favors a cautious approach and seeks to punish the oil and gas industry through penalties and increased taxes. The Obama administration in particular wants to shift the US gradually away from fossil fuels, in part through subsidies for renewable energy sources.

On March 16, Rep. Doc Hastings (R-Wash.), chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, announced his intention to file legislation to accelerate permitting in the Gulf of Mexico. In a parallel move, Democratic Sens. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) plan to file counter-legislation to mandate that Gulf of Mexico operators develop “diligently” the more than 41 million acres that have been leased, but are not currently under development.

SPILL CONTAINMENT OPTIONS

In response to BOEMRE’s mandate for containment of potential spills, the industry is progressing two parallel options developed by the Marine Well Containment Corporation (MWCC) and the Helix Well Containment Group (HWCG).

MWCC. This $1 billion non-profit entity was formed by a partnership of majors operating in the Gulf of Mexico including Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Shell and BP, with ExxonMobil leading the effort. The latest operators to join the MWCC are Apache, Statoil and BHP Billiton. In mid-February, the group released its interim containment solution (Fig. 1), which is capable of operating in water depths to 8,000 ft and has storage and processing capacity for up to 60,000 bopd and 120 MMcfd. The capping stack has a maximum operating pressure of 15,000 psi.

Both Interior Secretary Salazar and BOEMRE Director Bromwich toured the MWCC facility in late February. An expanded version of the containment system is expected to be released in 2012 that will be capable of operating in 10,000-ft depth with increased capacity of 100,000 bopd and 200 MMcfd. The expanded system will have a 15,000-psi subsea containment assembly with a three-ram BOP stack, dedicated capture vessels and a dispersant injection system.

HWCG. This group of 20 independent E&P companies operating in the Gulf of Mexico launched a containment solution based upon the equipment used by Helix to contain the Macondo spill. The Helix Fast Response System consists of a subsea shutoff device/well cap and intervention riser system, the Q4000 semisubmersible well intervention vessel, the Helix Producer I ship-shaped FPSO and associated risers, Fig. 2. It is currently capable of containing 10,000 bpd from spills in water depths up to 5,600 ft, with plans to substantially increase its capabilities over the next few months to capture and processing of 55,000 bopd and 95 MMcfd, at water depths up to 8,000 ft.

API Center for Offshore Safety. In response to the presidential oil spill commission’s recommendation, the American Petroleum Institute is launching a new Center for Offshore Safety as part of its global industry standards group. The center is expected to have independent staff and offices. The presidential panel’s proposal is patterned after the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, which was established after the Three Mile Island nuclear power accident in 1979.

The center will focus on implementation of API’s Recommended Practice 75, covering safety and environmental management systems, which was recently made mandatory by BOEMRE under the Workplace Safety Rule.

DRILLING ACTIVITY

Perhaps the most significant drilling activity that took place in the Gulf of Mexico during 2010 consisted of the two relief wells that BP drilled for bottom kill of the Macondo well through August and September. Cement pumped through one of the relief wells finally killed the Macondo well on Sept. 19 after it had been flowing for five months.

At least four drilling rigs have left the Gulf of Mexico since the moratorium began, a few have been stacked and a few others are either treading water on standby status waiting for permits to come through or staying active through workover projects. Table 1 presents the current deepwater rig activity in the Gulf.

The moratorium forced many oilfield operators and service companies to reallocate their Gulf of Mexico resources to other parts of the world, including offshore Brazil and West Africa. The smaller operators and service companies, who only worked in the Gulf of Mexico, have suffered revenue losses and resorted to personnel reductions.

| TABLE 1. Deepwater Gulf of Mexico rig activity as of March 25, 2011 |

|

However, permitting has begun to pick up (Table 2), albeit at a much slower pace than before Macondo. According to BOEMRE, as of March 25 five new well permits had been issued since the end of the moratorium, out of 28 applications submitted to the agency for water depths of 500 ft or more (the agency’s definition of deep water). Of the 28 applications, 14 were submitted before the moratorium ended on Oct. 12 and 14 after. Twelve “revised new well” permits were issued, involving a change to the well plan, out of 20 applications. In less than 500 ft, 39 new well permits and 88 revised new well permits have been approved, out of 59 and 90 submissions, respectively.

BOEMRE’s numbers, however, include many permits grandfathered in under the old regulatory regime. As detailed below, by March 25 only five new deepwater well permits had been issued under the new regulatory requirements, all of them within a single month.

Noble Energy. The first deepwater drilling permit under the new rules was issued to Houston-based Noble Energy on Feb. 28 for the resumption of a well on its Santiago prospect. The well, located in 6,500 ft of water about 70 mi southeast of Venice, La., had been launched just four days before the Macondo well blowout. Noble had drilled to a depth of 13,585 ft before being forced to plug the well due to the moratorium. The permit allows Noble to drill a bypass well that will maneuver around the plugs in the original well. Using the Ensco 8501 semisubmersible, the company plans to reach a target depth of 19,000 ft.

As part of its permit application, Noble estimated its worst-case spill to be 69,700 bopd. It has contracted with the Helix Well Containment Group to use its containment system in case of a spill. “This permit was issued for one simple reason: The operator successfully demonstrated that it can drill its deepwater well safely and that it is capable of containing a subsea blowout if it were to occur,” said BOEMRE’s Bromwich in a statement.

Drilling is planned to recommence in April, with results expected by the end of May. Although Noble operates the Santiago prospect with a 23.25% interest and is responsible for all drilling decisions, it is noteworthy that the prospect’s largest part-owner is BP with 46.5%. The other partners are Red Willow Production Company (20.25%) and Houston Energy (10%).

BHP Billiton. On March 11, BOEMRE granted Australian mining giant BHP Billiton a permit to resume drilling of a production well on its Shenzi field in Green Canyon block 653. The company had begun drilling the SB201 well, located in 4,234-ft water depth about 120 mi south of Houma, La., last February, two months before the Macondo blowout. Like Noble, BHP has signed on to use the Helix well containment system as its spill contingency.

When completed, the well will produce to the stand-alone Shenzi tension-leg platform, which began producing in 4,300 ft of water from seven wells in March 2009 and achieved a sustained production rate of 120,000 bopd within a year. Two additional wells are shut in and available for production when needed. The full field development plan calls for a total of 15 production wells with associated water injectors in Green Canyon blocks 609, 610, 653 and 654. BHP operates the field with 44% interest, while project partners Hess and Repsol hold 28% each.

ATP. On March 18, Hosuton-based ATP Oil & Gas received BOEMRE’s third permit under the new rules, allowing it to continue drilling the final phase of its No. 4 well on Mississippi Canyon block 941, located in 4,000 ft of water about 90 mi south of Venice, La. Initial drilling on the well began in August 2008, and the well reached a depth of 12,000 ft before drilling was suspended and the well was cased in July 2009. A rig was on location in April 2010 to prepare for installation of a production facility when the first drilling suspensions imposed in the wake of Macondo brought activities on the well to a halt.

| TABLE 2. Gulf of Mexico drilling permits issued as of March 25, 2011 |

|

The ATP Titan, a deep-draft floating drilling and production platform employing a unique triple-column spar design, will drill the No. 4 well to a TD of about 20,000 ft and will produce the well as part of the company’s 100% owned and operated Telemark Hub development. Like the first two companies with post-Macondo deepwater permits, ATP chose the Helix well containment system as its spill contingency.

Two other Telemark Hub wells, Mississippi Canyon 941 No. 3 and Atwater Valley No. 4, already produce to the Titan. A fourth well, Mississippi Canyon 942 No. 2, was also partially drilled to 12,000 ft before the oil spill and is awaiting approval to continue to TD.

Because the first three permits were for wells that were already being drilled before the moratorium went into effect, resumption of work on them faced fewer regulatory hurdles than drilling projects that have been proposed since the spill. BOEMRE announced in January that 16 projects by 13 companies that had been underway when the moratorium was imposed would not have to undergo new environmental assessments before restarting. Noble, BHP and ATP were among the companies mentioned. The agency has about 95 drilling applications pending. As permits are received, many of the following operators will resume their drilling activities.

ExxonMobil. The fourth drilling permit granted in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, the first to sanction a new well, is also for the deepest water depth yet. The permit, approved March 21, will allow ExxonMobil to drill an appraisal well in nearly 7,000 ft of water at its Hadrian North prospect in Keathley Canyon block 919, located about 240 mi off the Louisiana coast south of Lafayette. Exxon contracted the Marine Well Containment Corporation (of which it is the operator) for spill containment, marking the first time the MWCC containment device has been approved in a drilling permit.

After a gas discovery at Hadrian South, Exxon made what it described as a “large oil discovery” in early 2010 with a wildcat at Hadrian North. The prospect was planned for a four-well development, and a rig was on location with an approved permit to drill in April 2010 when activities were suspended after the Deepwater Horizon explosion. Exxon, which operates the prospect with a 50% interest, also has a permit pending for a second appraisal well there. Petrobras and Eni each hold 25% interest.

The Hadrian well will probably be the first of the newly permitted deepwater wells to be drilled, as the Maersk Developer semi-submersible was already en route to the prospect as of March 21.

ExxonMobil is also processing large-scale, wide-azimuth seismic surveys between its Hoover-Diana development, BP-operated Tiber field and Shell-operated Great White, in order to facilitate exploratory drilling in the area. A development well at Hoover/Diana had been planned last year to sustain the 10-year-old project’s production levels of 80,000 bopd and 200 MMcfd, but was postponed due to the moratorium. The development lies in water depth of 4,800 ft on East Breaks block 945 and Alaminos Canyon 25, about 160 mi south of Galveston, Texas.

Shell. The same day as ExxonMobil’s drilling permit was issued, Shell received the first BOEMRE approval under new regulatory requirements for a deepwater exploration plan. The plan calls for three exploration wells on Shell’s Cardamom Deep prospect in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, located at 2,950-ft water depth about 130 mi offshore Louisiana. In accordance with new regulatory requirements, a site-specific environmental assessment (SEA) was prepared and reviewed by BOEMRE before approval was granted, despite the fact that the planned wells are on a lease for which an original exploration plan—for Shell’s Auger field—was approved in 1985.

Before Macondo, similar plans to add wells to existing leases were often granted categorical exclusions that waived the requirement for further environmental assessment beyond the lease’s original National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review, even as the wells drilled on the lease became increasingly complex and challenging. Last August, BOEMRE announced that it would greatly restrict its use of categorical exclusions while it reviews its NEPA process.

In the case of Cardamom Deep, the agency said its review of the new SEA—which included scientific information not available in the original NEPA review—found no evidence that the proposed activity would significantly affect the quality of the human environment, and therefore a full environmental impact statement (EIS) was not required. Shell will still need drilling permits for each of the three wells planned; it has already submitted an application for the first well to BOEMRE. Meanwhile, the Houston Chronicle has reported that several environmental groups are considering lawsuits to prevent exploration from going forward on the grounds that BOEMRE violated NEPA by waiving the EIS.

|

|

Fig. 3. Intermoor in mid-March installed two subsea trees at the Mandy development in the Gulf for LLOG Exploration Company.

|

|

Cardamom Deep, located on Garden Banks block 426, was discovered with wells in 2009 and early 2010, and is estimated by Shell to hold up to 100 million boe. According to its exploration plan, the company would use the MWCC system in the event of an uncontrolled blowout, which the plan estimates could initially spill 143 million bpd and would take 109 days to stop with a relief well alone.

Other Shell drilling projects that were postponed due to the moratorium last year include a new well to expand the Tobago development in over 9,600 ft of water, appraisal and development drilling at the Vito discovery at about 4,000-ft water depth, and an appraisal well at Appomattox field in about 7,100 ft of water.

Chevron. Continuing the rapid-fire string of post-Macondo “firsts,” BOEMRE on March 24 issued the first wildcat permit to Chevron for its Moccasin prospect. Like the first three deepwater wells permitted, this fifth well, on Keathley Canyon block 736, was already spudded last year before being suspended in the wake of the spill. Located about 190 mi southeast of Houston, the field lies in 6,750 ft of water. Chevron operates the block with a 65% interest. Based on promising seismic data and proximity to the company’s huge 2009 Buckskin discovery 5 mi to the northwest, drilling began in March 2010 using Transocean’s new Discoverer Inspiration drillship with a planned TD of about 22,000 ft, but was halted in early June due to the moratorium. The rig, still contracted to Chevron at a day rate of $494,000, is likely to return to work at the wildcat in the coming weeks. MWCC will provide the spill contingency.

Others. In October, Hess took over operatorship and 20% ownership of Tubular Bells field from BP, increasing its share to 40% at a cost of $40 million. Chevron holds a 30% share in the deepwater field 135 mi southeast of New Orleans, and BP retains 30%. As drilling permits are granted, Hess is planning to advance the project to the sanction phase. The company has also applied for a permit to drill the No. 3 well in its 100% owned deepwater Pony prospect.

As a result of the moratorium, Newfield has deferred its exploratory drilling programs for 2011. However, the company is planning to commence production from several fields.

McMoRan put deep gas prospects in the Gulf’s shallow water back on the map with its Davy Jones discovery in just 20 ft of water early last year. The independent found a new hydrocarbon-bearing interval at over 27,000 ft TVD this February with its second Davy Jones well. Other deep prospects being explored by the company in the Gulf include Blackbeard East and Lafitte.

Apache’s Gulf of Mexico portfolio grew significantly during 2010 with the June acquisition of Devon’s shelf properties and Mariner Energy’s 36 deepwater projects. As a result, Apache holds nearly 840 blocks of producing and exploration leases in the Gulf of Mexico, representing almost 21.7 million acres. The company has received 25 drilling permits in 2011 to continue its shallow-water projects.

Holding more than 3 million lease acres in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, Anadarko has a portfolio of 32 discoveries, including Lucius, Shanandoah, Coronado, Samurai and Vito. The company has identified more than 100 prospects for drilling to target, with 100 million boe of oil and gas resources, provided it receives the drilling permits.

PRODUCTION ACTIVITY

While existing production continued unabated during the moratorium, the US Energy Information Administration expects output from the federal portion of the Gulf of Mexico to fall by 240,000 bopd in 2011—about 15% from 2010 levels—and by a further 200,000 bopd in 2012, ostensibly due to natural declines and the absence of production additions as a result of curtailed development drilling.

One of the more interesting developments that will take place during 2011 is the start of production from Petrobras’ Chinook and Cascade fields using an FPSO, the first in the Gulf of Mexico. The Minerals Management Service had provided an initial approval of the projects, but the final approval came March 17 from BOEMRE. One well from each of the two fields is ready to produce. Petrobras had planned to drill a second production well at Cascade before startup, but could not do so due to the moratorium.

The production vessel being used, BW Pioneer, has capacity to produce 80,000 bopd and 16 MMcfd and to store 600,000 bbl of oil. As a precaution against hurricanes, the FPSO has a disconnectable turret that can be disengaged in the event of an approaching storm. Located 165 mi offshore Louisiana in 8,200 ft of water, the field is far from the Gulf’s oil pipeline network. While other Gulf operators have built pipelines for similarly remote developments, such as Shell’s Perdido, the FPSO production scheme chosen by Petrobras has had success at the company’s deepwater fields in Brazil, and is in common use outside the US. Natural gas will be exported via pipeline to comply with the Gulf’s anti-flaring policy.

Apache is ready to start production from its Balboa deepwater oil and gas subsea tieback development on East Breaks block 597, but is waiting on a permit from BOEMRE.

Louisiana independent LLOG is planning to develop five discoveries in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico during 2011–2012. The company plans to install a floating production platform on its Who Dat development on Mississippi Canyon (MC) blocks 503, 504 and 547. For its Mandy development in MC 199, LLOG is planning to drill two discovery wells in the second quarter of 2011 and tie back to the Matterhorn tension-leg platform (TLP) in MC 243, Fig. 3. The company expects to produce from its Anduin discovery in MC 754, Marquette facility in Green Canyon (GC) 52, and Condor discovery in GC 448 during the first half of 2011, and the Goose development in MC 751 in the first quarter of 2012.

During 2010, Shell started production from its Perdido development. Next on the company’s agenda in the Gulf of Mexico is the Mars B project. A final investment decision (FID) was made in September to add a second TLP to Shell’s prolific Mars field, which will be installed at about 3,100-ft water depth to acquire production from the recent West Boreas and South Deimos discoveries starting in 2015. The Mars B TLP will be capable of processing 100,000 boepd. Also, during 2011–2012 Shell expects to make an FID on the Cardamom Deep project while front-end engineering and design (FEED) is underway for its Appomattox, Vito and Stones fields.

Chevron is expected to start up its Tahiti 2 project this year at a cost of $2.3 billion. Scheduled for startup in 2014 are Jack/St. Malo at $7.5 billon and Big Foot at $4.1 billion. Jack/St. Malo is an ambitious hub project with production capacity of 177 million boepd, and Big Foot will be TLP-connected with peak production capacity of 79 million boepd. Chevron also plans to make an FID for its Knotty Head and Mad Dog II projects in the near term.

2012–2017 LEASE SALES

With regard to the Gulf of Mexico, we are dealing with three different time scales. In terms of geologic time, one wonders how the Macondo spill will show up in a stratigraphic column centuries from now. On the scale of economic events, the US government’s response has been far too slow in the face of the opportunity cost and loss of production due to the successive moratorium and “permitorium.” On the other hand, the Obama administration is responding to the crisis on a political scale. The Democratic Party took a body blow in the 2010 congressional elections, but hopes that it can avoid the loss of the White House by clamping down on the oil and gas industry to prevent another oil spill before the 2012 presidential election.

BOEMRE has called for information and nominations for the lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico western and central planning areas for 2012–2017. The agency also intends to prepare a multi-sale EIS covering sale, which may have a dampening effect on the rules and conditions for E&P activity. Whether and when the administration will open up the eastern Gulf of Mexico—as it had been planning to do before Macondo—depends on the future course of political and economic events, as well as the safe operation of existing E&P projects. At the least, an obituary of the oil and gas activity in the western Gulf of Mexico would be premature.

|