Iraqi development plan breaks new ground

Beyond its enormous scale, the recent auction marks the first time so many development projects will target simultaneous completion dates. It also represents a major break from the prevailing NOC-IOC dynamic.

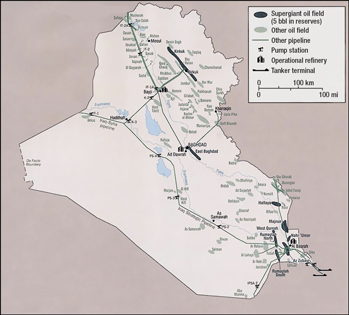

Beyond its enormous scale, the recent auction marks the first time so many development projects will target simultaneous completion dates. It also represents a major break from the prevailing NOC-IOC dynamic.Stan Harbison, Ben Montalbano and Lou Pugliaresi, Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc. In 2009, the government of Iraq held a competitive auction for the rights to develop 60 billion bbl of proved crude oil reserves across 10 major fields. The output requirements under the awarded contracts yield a production plateau of 9.6 million bpd by 2017 in addition to current production. By any standard, the Iraqi auction represents a major event in the history of the world oil market; it is the largest single transfer of petroleum reserves into the production stream since the beginning of the petroleum era. The US Energy Information Administration estimates Iraq’s proved reserves at 115 billion bbl (Fig. 1), ranking the country third in proven reserves behind Saudi Arabia and Iran. This number is derived from appraisals by the bidding companies of each of the fields put up for auction, which were then circulated among all of the bidding companies. The aggregate reserves of those fields were just short of 80 billion bbl. Very few countries have this type of data supporting their official aggregate reserve number, and no other countries in the Persian Gulf region.

Furthermore, before it was dismantled in 1987, the Iraq National Oil Company (INOC) had done evaluations of its reserves on several occasions over several decades. It posited a probable reserves figure over 200 billion bbl and potential resources over 400 billion bbl. These are estimates arrived at by relatively conservative assumptions. The production commitments among the winning bidders, through a contracting vehicle called technical service contracts (TSC), are only partially transparent. It is known that companies will receive a fee of $1–$2/bbl plus cost recovery of incurred capital, operational and supplementary expenditures. International oil companies have told the Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc. (EPRINC) that the Iraqi contracts provide them with double-digit returns of about 15%. Although such returns might also be available from other projects in company project portfolios with lower risk profiles, the IOCs likely view Iraq as also providing an opportunity to substantially improve returns through access to new ventures. The Iraqi government expects to receive over 95% of total revenues generated by the auctioned fields. This has already diffused early political opposition to the auctions as proposed. There are important unknown aspects of the contracts, such as how cost efficiency is rewarded and the unresolved issue of responsibility for making massive logistical and infrastructure investments. Admittedly, a large array of external and internal threats and more traditional obstacles could derail Iraq’s prospects for a massive increase in crude oil output. Nevertheless, Iraq’s potential to bring about a “supply shock” to world oil supplies can no longer be dismissed out of hand. An alternative view is that expanded Iraqi production may provide essential new supplies to prevent a “price shock” if non-OPEC production experiences sustained output declines. In this scenario, the role of Iraqi supplies may be more as a brake on rising prices than a catalyst to a lower price path. In any case, the Iraqi auction clearly opens the door for a careful review of the conventional wisdom on the outlook for oil prices over the next 20 years. POTENTIAL PRODUCTION PROFILES Figure 2 outlines Iraqi production growth under two scenarios. As stated above, 9.6 million bpd is contracted to come online by 2017 in addition to current production of roughly 2.4 million bpd, bringing total Iraqi production to 12 million bpd in 2017—equal to Iraq Oil Ministry expectations. However, EPRINC anticipates delays and has built them into its production estimates. The first scenario assumes that contracted plateau volumes will be delayed until 2020 rather than the contracted date of 2017; in the second scenario, only 75% of contracted volumes are available by 2020.

The scenarios outlined in Fig. 2 clearly raise the potential for downward price adjustments in crude oil against a range of business-as-usual cases. Even a relatively modest shift in long-run prices would provide enormous benefits to the US economy. A sustained decline in oil prices of just $20/bbl (from any likely forecast level) would confer present-value savings for the US economy of over $1 trillion—a large sum even by current standards. (A simple present-value calculation on imports alone—currently 10 million bpd—yields annual savings of about $73 billion/year. Using a discount rate of 5% over 25 years yields well over $1 trillion in savings assuming a constant import level.) Because the potential for lower oil prices from new Iraqi production is substantial, several of the likely price outcomes may also place alternative transportation fuels into severe financial stress. Biofuels, for example, which face marginal economics even at oil prices in the range of $80/bbl, will require additional subsidies at lower oil prices; such subsidies may not be easily obtained in an era of “fiscal fatigue.” HISTORY Iraq’s oil industry has been arguably the most constrained in the world. In the 60 years preceding the auctions, the Iraqi oil industry had functioned successfully for only seven years. It was owned and operated from the late 1920s until its nationalization in 1972 by the Iraq Petroleum Company, a consortium of four IOCs. The preferences of some of these companies to increase production in other concessions led to an artificially slow development of Iraqi oil. From the end of World War II until 1972, Iraqi production lagged far behind that of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Iran. In the seven years following nationalization, Iraq’s national oil company raised production to 3.5 million bpd from 1.4 million bpd, a 150% increase, Fig. 3.

The ascendancy of Saddam Hussein’s regime led to a succession of international conflicts that capped further growth of the industry. This continued through the US invasion and occupation of Iraq. During the past several years, the emergence of an Iraqi government did not alleviate the industry’s endemic problems: reservoir damage in its two largest producing fields, a severe shortage of required equipment and the inability to purchase needed equipment and expertise. THE AUCTION More than 40 companies were prequalified for the auction’s first round in mid-2009. The initial auction did not go well. It was clear that the government and the companies had widely different perceptions of the contracts’ value. Only one of eight fields reached a contracted agreement in the first round, and only after a 50% increase in the bid price. Several months after the first round, apparent contractual adjustments by the oil ministry and flexibility by the majors resulted in a turning point in the auctions. Failed bids on two supergiant fields in the first round were adjusted and accepted. As it turned out, the bids on those fields set the prices that prevailed in the second round. It is clear that there were adjustments in contractual terms after the first round, but those changes have never been acknowledged. There have been references to a substantial change in the method of applying the income tax. That change is large, but does not fully explain the willingness of all companies to increase the effective price paid by well over 50%. In both the first and the second rounds, the bidding companies far exceeded the target volumes proposed for the production plateau by the oil ministry. This occurred despite their low weighting of volume (20%) versus other criteria in the auction process. The Iraqi government evaluated each company’s bid using criteria that include production fees, production volumes and production timeframes. By bidding aggressively high production volumes and low per-barrel production fees, the companies’ bids became immensely more valuable to the Iraqis. The most important result was an increase of over 5 million bpd in incremental target production compared with the government’s expectation. This change explains the sudden (and somewhat problematic) jump in the ministry’s forecast of plateau volumes. Iraq’s long-held belief that it could increase production to 6–7 million bpd suddenly jumped to 12 million bpd. This higher plateau level is highly optimistic, but it is important to remember that achieving those volumes on a stipulated timetable is contractual. Figure 4

News from the winning consortia has focused on overall capital spending budgets, which were part of each field’s contract. The contracts included estimates of the number of expected wells drilled and rig tenders. Although planning will be the focus of the first year for developing these projects, organizing the drilling program will be given a high priority in increasing field production. Appraisal and seismic work will take place ahead of most of the drilling, and professionals in those areas are already in Iraq. ANTICIPATED DIFFICULTIES AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS The unprecedented scale of the Iraqi government’s commitment combined with long and sophisticated experience in project management among many of the winning bidders offers considerable potential for the field development effort to move forward quickly. Some of the difficult political issues have been met in the auction decision and process; others are being met, if grudgingly, by the very large and unexpected revenues that pending legislation would distribute on a per capita basis among Iraqi provinces. The pitched rhetoric between the Kurdish government and the central government has softened, but substantial areas of disagreement remain. In line with their historical pursuit of autonomy, the Kurds have initiated and want to pursue a separate energy enclave. Under the proposed revenue distribution structure from the central government, the Kurdish government would receive 17%—much more money than the Kurds are likely to achieve from their regional oil development program. Security issues are also political issues. It is agreed that violence has been sharply reduced in the past three years, but it remains unacceptably high. Ongoing attacks are centered in the Baghdad area and to its north. Fields there, including the two supergiant Kirkuk and East Baghdad Fields, never received acceptable bids. Nearly all of the fields that will be developed are in southern Iraq. The companies have not been deterred by security concerns there, though some may exist. Managing and developing new infrastructure is the greatest challenge. Bottlenecks are certain to occur. Delays in obtaining rigs will no doubt be a problem. Developing a system for bringing water from the Gulf for secondary recovery will require a very large common effort by the companies. Much of the infrastructure will be centered on the fields, where its costs will be recoverable as production increases. The government has charged itself with repairing and expanding Iraq’s oil pipeline system and oil ports. Large engineering contracts have been awarded to upgrade and expand Iraq’s oil ports in the Gulf. That process will need to continue, as large volumes of oil will need export facilities in just three years. The costs of pipelines and ports are high, and the government’s record on timely processing of payments is not exemplary. It remains to be seen if that process moves along at a sufficient pace. Beyond its enormous scale (more than 60 billion bbl of oil contracted for development), the auction breaks new ground in two crucial ways. First, it is the first time in industry history that so many development projects of this size will be initiated at the same time, with target completion dates at the same time. If the Iraqi auctions meet three-quarters of the contracted volumes, they will surpass even Saudi Arabia’s massive production expansion of the 1970s, Fig. 5.

Second, the auction represents the first significant break from the prevailing oil industry structure in almost 40 years. Since the wide-scale nationalization of the 1970s, oil companies have had limited ability to explore for or develop oil reserves in countries with NOCs. This has been especially true in the Persian Gulf region, where the world’s largest reserves are located. The Iraqi auction is a rare marriage of the interests of oil companies and those of a government that controls a very large reserve base. Large multinational oil companies can often bring a unique set of technical skills and efficiencies in managing large-scale and complex development projects, as well as the capital needed to do so. Iraq has large reserves and a great need for revenue. With the current auction, Iraq has established a format for reserves development that leapfrogs the models of the other major Gulf oil producers—a transparent contractual arrangement that offers international companies an acceptable return on investment. Winning bidders included both NOCs and publicly held IOCs. It is difficult to determine whether the government demonstrated a preference for either type of company in selecting auction winners. However, the Iraqis ended up with a broadly based international group of companies, including operators from Russia, China, the US and Europe. Such diverse representation may prove useful not only in providing a mix of approaches to field development, but also in ensuring widespread international support for the projects to remain free from real and imagined threats. CONCLUSIONS In recent years much of the debate over peak oil has moved from a discussion of below-ground concerns (geology) to above-ground concerns (politics and resource nationalism). While geology is difficult to change, above-ground problems can move quickly from a negative to a positive outlook (and vice versa). The addition of Iraq’s proposed new production seems certain to delay a peak in oil production, whenever that may occur. While the Iraqis are moving in the right direction, a large portfolio of risks remain, including the absence of a comprehensive law justifying the legal framework for the auctions. Contract risk has been identified by the companies as significant. The struggle for political leadership as evidenced by the recent parliamentary elections highlights that risk. Both the Kurdish-Arab struggle for Kirkuk and the oil and gas resources in Kurdistan will remain very serious political risks. Outstanding Iraqi debts to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the UN have yet to be resolved and could create problems down the road. Several major oil companies, which chose not to bid, were unable to get comfortable with the lack of clarity on performance conditions of the contracts, the stability of the tax regime, and the large carried interest of the Iraqi NOC (approximately 25%) in the fields won by the bidders. In addition, large-scale challenges remain in getting sufficient rigs into Iraq; scheduling, building and financing an adequate and coordinated export capacity, including ports and pipelines; and securing sufficient water for enhanced recovery. None of these uncertainties are insurmountable, but resolving all of these issues is critical if the Iraqis are to move forward with reasonable speed on their ambitious production program.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Oil and gas in the Capitals (February 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Dallas Fed: E&P activity essentially unchanged; optimism wanes as uncertainty jumps (January 2024)