Drilling advances

Planning for Arctic drilling

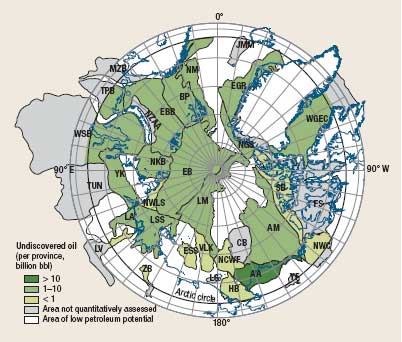

Planning for Arctic drilling Many of the world’s untapped petroleum resources lie in polar regions. Antarctica and the surrounding ocean are reserved for basic scientific research and are off limits to mineral exploration by international treaty. The Arctic by comparison is wide open. Although covered by water and sea ice, it is surrounded by energy-hungry nations. According to James Parker of Shell International Exploration and Production, in a presentation at the Arctic Sea Study Tour in the Bodø Graduate School of Business this March, the area to be explored is vast: some 8 million km2 of land and 14 million km2 of ocean are within the Arctic Circle. Thus far, 400 fields have been discovered in this region, mostly onshore, holding 240 billion boe in reserves. According to the US Geological Survey, 25 of the 33 geological provinces are estimated to hold 412 billion boe: 90 billion bbl of oil, 1,669 Tcf of gas and 44 billion bbl of NGL in undiscovered resources, Fig. 1. Drilling for these will be done by polar-class vessels, semisubmersibles or drillships. The drilling operation itself is not beyond the industry’s capabilities; far from it. The industry has continued to perfect the “pad” drilling concept for land and already has subsea template technology that it routinely applies. Harrison et al. examined the industry’s progress and demonstrated that in 1970 a 20-acre wellsite could only reach an area of 502 acres (0.8 mi2) at 10,000 ft. This was compared to the reach possible in 2005: a six-acre wellsite could reach 32,170 acres (50 mi2) at 10,000 ft. That represents a 60-fold increase in subsurface reach with a two-third reduction in surface area for land operations.1 Extended reach drilling technology has expanded the drilling envelope even farther in the intervening years. What has constrained the industry’s move to find and develop the potential resources is the need to overcome the competing forces in the Arctic. Problems are many. Physical constraints include ice (both sea ice and glacial flows), remoteness, extreme temperatures and permafrost. Social and environmental sensitivity and its relatively pristine condition are other factors. There are also the legal constraints of national boundaries (some disputed) and competing jurisdictions. Numerous JIPs have been underway since 2000 to address the industry’s needs and impacts, so that it can operate responsibly. Most prominent are discussions that deal with oil spill potential. A January 2009 report, “Opening the Arctic Seas,” issued by The Coastal Response Research Center, reviewed the findings of a 2008 conference that explored five Arctic oil spill scenarios.

The scenarios resembled incidents that have already occurred. The drillship scenario would affect birds, marine mammals and shellfish as well as Ivvvavik National Park and Herschel Island, Yukon Territory, Canada, and the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge. Several existing policies/laws apply in the US and Canadian jurisdictions including IMO guidelines for ships operating in ice-filled waters, Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (US), Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (US), Jones Act (US) and US plans including National Response Plan, State of Alaska Planning and the Joint Unified Contingency Plan. Canadian laws invoked would include: National Response Plan, Canada Fisheries Act, Canada Shipping Act and Canadian Coast Guard National Response Plan. Joint plans include Canada-US Marine Spill Pollution Contingency Plan and Canada-US North Plan.

While these laws and commercial responses would generate manpower and equipment to handle the emergency, the attendees did find response gaps. Also, there are no established places that could accept a damaged ship, and special government approval would be needed to use dispersants or in situ burning. Staging areas are few: Kaktovik in the US has a small population and few resources. In Canada, the closest town, Tuktoyaktuk, is similar. Logistics would be difficult and disrupt the communities. Prudhoe Bay has resources, but is 200 mi away and not acceptable for daily operations. There might also be communication problems. Much thinking and planning has already occurred to understand the complex of problems and needs that high-latitude oil industry operations will create. Drilling into the Arctic’s subsurface will not pose a problem, but surface logistics will require significant new physical and political structures. 1 Harrision, W., “Current environmental practices in petroleum exploration and production,” in Lee, C., et al., eds., Energy and the Environment: A Partnership that Works: Actual Impacts of Oil and Gas Exploration and Development on our Environment, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Tulsa, March 2005.

|

||||||||||

- Coiled tubing drilling’s role in the energy transition (March 2024)

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- Shale technology: Bayesian variable pressure decline-curve analysis for shale gas wells (March 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- Using data to create new completion efficiencies (February 2024)

- Digital tool kit enhances real-time decision-making to improve drilling efficiency and performance (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)