To date, 155 countries and the European Community have joined in the Convention. The United States ratification awaits Senate advice and consent.

Paul Kelly, Consultant

The offshore oil and natural gas industry spends billions of dollars annually in the search for, and production of, oil and gas in the world’s oceans. US offshore production accounts for more than 27% of the country’s oil production, and 15% of its natural gas production. Each year, offshore energy development contributes between $4 and $6 billion in revenues to the federal treasury. Millions are also paid to states and local communities. The federal offshore produced about 500 million barrels of oil and about 3 trillion cubic feet of gas in 2006.

In addition to activities in areas under US jurisdiction, such as Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico, the US has substantial interests in offshore oil and natural gas development activities globally, given the nation’s significant reliance on imported oil. US oil and gas production companies, as well as drilling, equipment and service companies, are important players in the competition to locate and develop offshore gas and oil resources. The pace of technological advancement, which drove the need to define the outer limits of the continental margin, has not abated and is taking us to greater water depths and rekindling interest in areas that once were considered out of reach or uneconomic.

FOUR DECADES OF INDUSTRY SUPPORT

Recognizing the importance of the Law of the Sea (LOS) Convention to the energy sector, the National Petroleum Council, an advisory body to the US Secretary of Energy, in 1973 published an assessment of industry needs in an effort to influence the negotiations. Entitled Law of the Sea: Particular aspects affecting the petroleum industry, it contained conclusions and recommendations in five key areas including freedom of navigation, stable investment conditions, protection of the marine environment, accommodation of multiple uses, and dispute settlement. The views reflected in this study had a substantial impact on the negotiations, and most of its recommendations found their way into the Convention in one form or another.

Having been satisfied with the terms of the Convention, all of the US oil and gas industry’s major trade associations have for many years supported ratification of the Convention by the US. Also, the Outer Continental Shelf Policy Committee, an advisory body to the US Secretary of the Interior on matters relating to offshore oil and gas leasing program, has adopted resolutions supporting US accession to the Convention.

OFFSHORE RESOURCES

The Convention is important to our industry’s efforts to develop offshore oil and gas supply worldwide. It secures each coastal nation’s exclusive rights to the living and non-living resources of the 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). It would bring an additional 4.1 million square miles of ocean under US jurisdiction. This EEZ is an area larger than the US land area. The Convention also broadens the definition of the continental shelf in a way that favors the US, with its broad continental margins, particularly in the North Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, the Bering Sea and the Arctic Ocean.

EXPLORATION MOVING INTO DEEPER WATERS

Offshore petroleum production is a major technological triumph. We now have world record, complex development projects that are located in 8,000 ft of water in the Gulf of Mexico (In June 2007, gas production started on Independence Hub, a semisubmersible platform operated by Anadarko). This was thought unimaginable a generation ago. Even more eye-opening, a number of exploration wells have been drilled in the past three years in over 8,000 ft of water and a world record well has been drilled in over 10,000 ft of water.

New technologies are allowing oil explorers to extend their search for resources of oil and gas out to and beyond 200 nautical miles for the first time, thus creating a more pressing need for certainty and stability in delineation of the extended shelf boundary. In addition, those technologies also allow that the largest discoveries in a generation can be made in field sizes not even imagined before.

Before the LOS Convention, there were no clear, objective means of determining the outer limit of the shelf, leaving a good deal of uncertainty and creating significant potential for jurisdictional conflicts between coastal states. Under the Convention, the continental shelf extends seaward to the outer edge of the continental margin or to the 200 nautical-mile limit of the EEZ, whichever is greater, to a maximum of 350 nautical miles in certain situations.

The US understands that such features as the Chukchi Plateau and component elevations, situated to the north of Alaska, could be claimed by the US under the Convention, which in turn could substantially extend US jurisdiction well beyond 350 nautical miles. US companies are interested in setting international precedents by being the first to operate in areas beyond 200 miles and to continue demonstrating environmentally sound drilling and production technologies.

IMPORTANCE OF DELINEATING THE EXTENDED SHELF

The Convention established the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (“the Continental Shelf Commission”), a body of experts through which nations may establish universally binding outer limits for their continental shelves under Article 76. The objective criteria for delineating the outer limit of the continental shelf, plus the presence of the Continental Shelf Commission, should substantially reduce potential conflicts of neighboring coastal states and provide a means to ensure the security of tenure crucial to those investing in capital-intensive deepwater oil and gas development projects.

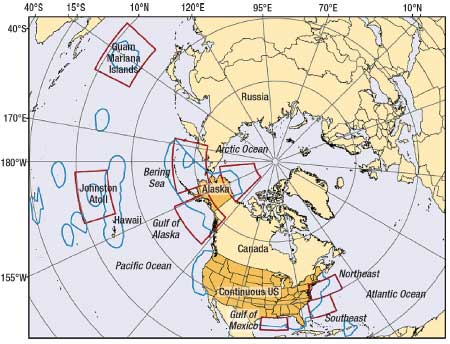

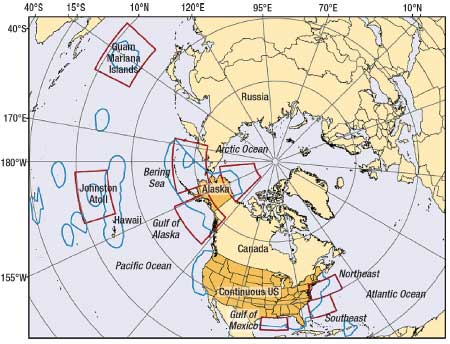

It is in the best interest of the US to follow the Convention’s procedure for establishing the limits of its continental margin beyond 200 nautical miles. Where appropriate in so doing, the US could expand its areas for mineral exploration and development by more than 291,383 square miles. The US needs to carry on with the mapping work and other analyses and measurements required to substantiate the extent of its shelf. Some of the best technology for accomplishing this resides in the US. Establishing the continental margin beyond 200 nautical miles is particularly important in the Arctic, where there are a number of countries vying to expand their offshore jurisdictional claims. In fact, Russia and Norway have made submissions with respect to the outer limit of their continental shelf in the Arctic, while the US and Canada have taken symbolic actions demonstrating their interest in extended boundaries, Fig. 1.

|

|

Fig. 1. Eight regions (in red) adjacent to the US and its dependences, identified by Mayer et al. (2002), where there likely exists extended continental shelf (ECS) beyond 200 nautical mi (in blue), where bathymetric, seismic and geophysical data need to be collected. Regions in this figure result from academic study and do not represent a formal position of the US, and are without prejudice to any rights that the US has with respect to its continental shelf.

|

|

Denmark will be asserting claims beyond Greenland’s shelf. Also, many countries that were parties to the convention in 1999 are waking up to a 2009 deadline for filing offshore jurisdictional expansion claim submissions on a massive amount of maritime territory as provided under the 1982 Convention. Only eight claims have been made to date, although about 50 coastal nations are bound by the May 13, 2009 deadline for submissions, which is 10 years from their date of acceding to the Convention. Russia was first to make a submission in 2001. Since then, Brazil, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, France, Spain, Norway and the United Kingdom have filed claims in whole or in part.

ARCTIC

The world was startled last summer when the Russian Federation symbolically planted a Russian flag on the seabed beneath the ice of the North Pole, emphasizing its claim to the region as an extension of the Russian continental shelf in waters 4,261 meters deep. Soon thereafter, Canadian Prime Minister Harper made headlines when he toured Canada’s Arctic region, emphasizing that Canada’s claims include sovereignty over the Northwest Passage. The US sent a survey vessel off the coast of Alaska.

In the Arctic, a key dispute is whether the Lomonosov Ridge, a vast underwater mountain range stretching across the North Pole, is an extension of Russia’s continental shelf, or part of Greenland, which belongs to Denmark, or neither one or both.

Such political moves should not have come as a surprise. The US Geological Survey estimates that about one quarter of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas lies beneath Arctic waters. Modern technology now makes it possible to harvest some of these resources. Securing access to these resources would not only help the US meet its own growing energy needs, but could eventually contribute significant royalty payments to the federal treasury.

HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE

The Continental Shelf Commission is expected to have a very heavy workload reviewing coastal state submissions over the next 12 months. By some estimates, in the years ahead, we could see an historic division of many millions of square kilometers of offshore territory with management rights to all its living and non-living marine resources on, or under, the seabed. An advisor to developing states preparing their own submissions said recently, “This will probably be the last big shift in ownership of territory in the history of the Earth. Many countries don’t realize how serious it is.”

How much longer can the US afford to be a laggard in joining this process? An American geoscientist would make a welcome addition to the Continental Shelf Commission and would have much to contribute. Asked recently about the competitive aspect of claims on Arctic territory, Liv Monica Stubholt, Norway’s deputy minister for foreign affairs, said that rather than point fingers at Russia, “Norway would prefer to see the US Senate ratify the 13-year-old UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which would give the US a seat on the commission and a stake in a non-belligerent resolution of competing claims.”

MARINE TRANSPORTATION

Oil is a global market with US companies as leading participants. The LOS Convention’s protection of navigational rights advances the interests of energy security in the US, particularly in view of the dangerous world conditions we have faced since the tragic events of September 11, 2001. About 44% of US maritime commerce consists of petroleum and petroleum products. Trading routes are secured by provisions in the Convention combining customary rules of international law, such as the right of innocent passage through territorial seas, with new rights of passage through straits and archipelagoes. US accession to the Convention would put it in a much better position to invoke such rules and rights.

GROWING OIL AND GAS IMPORTS

The outlook for US energy supply in the first 30 years of the new millennium brings home the importance of securing the sea routes through which imported oil and natural gas is transported.

According to API’s Petroleum Facts at a Glance for September 2007, total imports of domestic petroleum were 66%, or 13.76 million barrels per day. This is an extraordinary volume of petroleum liquids being imported every day.

The Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration (EIA), in its 2007 Annual Energy Outlook, projects that by 2030, net imports of crude oil are expected to account for 71% of crude supply, up from 66% in 2005.

EIA’s 2007 Outlook also states that, despite the projected increase in domestic natural gas production, over the next 25 years, an increasing share of US gas demand will also be met by imports. A substantial portion of these imports will come in the form of LNG. All four existing LNG import facilities in the US are now open, and three of the four have announced capacity expansion plans. Meanwhile, several additional US LNG terminals are under study by potential investors, and orders for sophisticated new LNG ships are being placed. This means even more ships following transit lanes from the Middle East, West Africa, Latin America, Indonesia, Australia and probably Russia, seeking to participate in the US natural gas market.

RISING WORLD OIL DEMAND

According to the EIA, world petroleum consumption in 2004 was 82.3 million barrels per day. By 2030, world demand is expected to reach nearly 118 million barrels per day. The Convention can provide protection of navigational rights and freedoms in all areas through which tankers transport oil and gas.

From an energy perspective, there are growing, potential future pressures in terms of marine boundaries, continental shelf delineations and in marine transportation. The LOS Convention offers the US the chance to exercise needed leadership in addressing these pressures and protecting many vital US ocean interests. The US petroleum industry is concerned that failure by the United States to become a party to the Convention could adversely affect US companies’ operations offshore other countries, and negatively affect any opportunity to lay claim to vitally-needed natural resources.

At present, there is no US participation, even as an observer, in the Continental Shelf Commission-the body that decides claims of extended continental shelf areas beyond 200 miles-during its important development phase. The US lost an opportunity to elect a commissioner in June 2007, and it will not have another opportunity to elect a Commissioner until 2012. By failing to ratify the treaty, the US is now watching from the outside as the guidelines and protocols for conduct on the world’s oceans are developed and as certain provisions of the Convention are implemented.

WHY THE CRITICS ARE WRONG

For many years, procedures by which the US Senate could exercise its responsibility to provide advice and consent for ratifying the Law of the Sea Convention were blocked by Senator Strom Thurmond, long-time chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who simply refused to allow acceding to the Convention to come to a vote. Senator Thurmond’s opposition was based on his belief that provisions of the treaty would remove the sovereignty of the United States and on a general distrust of the UN.

Initially, once Thurmond departed from the Senate, it was thought that the chances of approval of the Convention were much improved. In fact, since then, the Convention has been approved twice by the Foreign Relations Committee, most recently in October 2007 in a 17 to 6 vote. President Bush has also expressed his support for the Convention. Nevertheless, a small minority of Senate critics remain opposed to accession, continuing a strategy of procedural delays which, so far, have prevented the Convention from going to the full Senate Floor for a vote.

These members, surprisingly, and in the face of $100-plus oil, include avid critics from oilpatch states, such as Senators David Vitter of Louisiana and James Inhofe of Oklahoma. Their opposition centers around dispute settlement provisions in the Convention, their belief it could submit US military activities to external review, their belief that it may create private rights or provide for a cause of action in American courts, and in various other ways remove the sovereignty of the US.

The first thing that can be said in response to these critics is that the US military has strongly supported accession to the Convention for many years, and that successive Chiefs of Naval Operations, including the present Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, have repeatedly testified why ratification is important to US military interests around the world. It is difficult to understand how these critics can tell the US military that it does not know its business.

Furthermore, all the critics’ arguments have been soundly refuted by the finest international legal scholars in the land, including Professor John Norton Moore of the University of Virginia Center of Oceans Law & Policy which has published the definitive six-volume article-by-article analysis of the Law of the Sea Convention used by governments all over the world. After last October’s vote in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Professor Moore wrote to Senator Richard Lugar, Ranking Member of the Committee, that “under the well established foreign relations law of the United States, no Convention can set aside the sovereignty of the United States.”

This has not prevented the critics from repeating the same old erroneous arguments. Meanwhile, the petroleum industry, the telecom industry, the shipping, mining and fishing industries, as well as non-government environmental organizations, all stand by, united in disbelief at the critics’ naïveté and failure to grasp the consequences of their actions, as resource-bearing subsea lands all over the world get carved up into new ownership regimes without the participation of the US. I hope that the full Senate finally ends the squabbling and approves ratification of the Law of the Sea Convention before adjourning for the year.

|

THE AUTHOR

|

|

|

Paul L. Kelly is a consultant on energy and ocean policy, and a retired senior vice president of Rowan Companies, Inc., where he had responsibility for special projects, and government and industry affairs. He was a member of the US Secretary of Interior’s Outer Continental Shelf Policy Committee, serving as chairman of the Committee from 1994 to 1996, and he is a member of the Joint Ocean Commission Initiative. Mr. Kelly holds BA and JD degrees from Yale University.

|

|

|