Bit selection depends on performance, cost and locale

DRILLING BITSBit selection depends on performance, cost and localeIn the never-ending quest for higher scales of efficiency in drilling operations, bit selection is a variable component that can sometimes make a significant difference. World Oil asked a panel of four oil company engineers to describe the process by which they select premium or standard bits and under what circumstances

The engineer will want to know what the answers are to some of the inputs to the crucial cost/ft formula (see table), such as time on bottom, ROP and bit cost. In addition, there may be questions about whether bit-to-formation fit can minimize casing costs, as well as whether total well depth is a factor. To help sort out these factors and more – and to give insight into the manner by which they make bit selections – World Oil consulted a group of four drilling experts from major and independent oil companies, who have widespread experience in many locales. The panel includes:

Listed below are the panel’s thoughts on the various factors that go into selecting premium or standard bits. In general, the panel finds that performance outweighs bit cost. The group also gives its views on whether bit selection is a key decision in the overall drilling scheme.

Q. Who makes your bit selection, and at what time in the well planning and drilling process?Sarrafian: We have a series of alliances with manufacturers that provide us with bits, along with their expertise in bit selection. When the drilling engineer writes the drilling program, a lot of data and information is obtained with help from alliance partners. In most cases, the engineer reviews information from offset wells and comes up with the plan that he thinks is the best fit. The drilling supervisor and the engineer review the plan with the service company’s field representative to ensure that the particular bit selection is best for that area. So, as you can see, it is a three-to-four step process. Sibley: I make the bit selections. Most are selected from area bit performance through research, and then changed, when necessary, as a result of a bit’s dull condition and performance in the particular well when drilled. Calhoun: There is a general selection or narrowing down of alternatives in the well planning process. This is more specific or can be as specific as an exact bit/BHA specification for development wells (where we are high on the learning curve). During the actual well drilling, the onsite drill rep – either by himself or in discussions with rig personnel, a directional driller, a Chevron drilling superintendent or a Chevron operations drilling engineer – will make the decision, when they actually pick up the bit/BHA to run it in the hole. Hudspeth: We are split up into managers, superintendents and engineers. On a development well, the engineers make the selection. On the more critical exploratory and deep wells, the superintendents make the choice with the engineers’ input. Q. Does the bit selection process for a wildcat differ from a well in known areas?Sarrafian: I would say that it does, because a true wildcat by definition is a long way from any other wells, and you’ve got more uncertainty than you would if you were drilling the last well in a hundred-well field. Potentially, you would have to search more. . . . but the bit selection process really doesn’t change that much except, that your selection will have more contingencies for unplanned events. Sibley: Yes – we don’t have lots of information for wildcats. You don’t have run histories, bit grades, performance data, rock strengths or everything else. I mean, it’s just a matter of having data or not having data. Calhoun: Yes, with a wildcat there’s usually more uncertainty. Usually, what you’ll try to make available or make sure that you have available at short notice is a wider range of bits or bit choices. You want more bit alternatives, as we say, with a wildcat than with a development well (where it’s more like an assembly line process – you know exactly what bit you’re going to run at what interval). Hudspeth: No, not really. The reason for that is because we know what we have in offset and known areas. We would rather go ahead and put something in the hole, for which we have an idea about how it’s going to perform.

Q. Is it more "conservative" relative to buying more "durable," more expensive bits for unknown conditions?

Sarrafian: I can’t say it is more conservative. We try to geologically relate our well to the closest available information and make the appropriate bit selection for each section of the well. Sibley: Yes, meaning that I would probably throw more money at bits in an unknown region, because the operating costs are expected to be higher. Also, poor performance for less expensive bits is more likely with selection variables unknown. It gets to be a cheap insurance-type issue to have a premium bit in the ground. Calhoun: Probably. Sometimes, buying durable and/or more expensive bits is prudent. Usually, you would tend to err on the more durable, harder application style of bit. Hudspeth: No. I wouldn’t say that it’s more conservative. Our philosophy is that no matter what the bit cost is, we are just trying to get more bang for our buck. If it’s going to be a so-called premium bit, and we find that it’s going to stay in the hole longer and give us a lower cost/ft, we’ll go ahead and go with it. This is regardless of whether we’re drilling an exploratory or development well.

Q. Do you place more emphasis on performance than on relative bit costs?Sarrafian: We try to achieve highest total value. The bit price is important, but overall performance is just as important. So, putting the two together, in terms of cost/ft, will determine the best option. Sibley: That’s tricky. I’d say in most cases, cost/ft is the ruling factor. I guess, in a nutshell, I look at my cost curve rather than my days curve. You want to drill cheaper, not necessarily faster. So, if it costs a "million dollars" to have a performing bit, I’m not going to run that bit, simply because it’s not cost-effective. Calhoun: It varies, just depending on the local operations. Chevron has a number of operating companies throughout the world, and each has its own drilling staff and style that are autonomous. They really have all the authority to make their own decisions on well programing and bits. Depending on the nature of the personnel and business drivers, sometimes they’ll be more performance-oriented or willing to take risks. Sometimes, they’ll be much more conservative and risk-averse. Hudspeth: Yes, we do. We go on performance, because, at the end of the day, it lowers our entire cost/ft. Q. Are higher quality bits typically worth their costs? How do you judge this – by longer runs, fewer trips, hole quality, etc.?Sarrafian: All of the above factors go into creating total value. For example, a bit run of only 10 hr in a deep well would not be economical, because you would spend more time tripping than drilling. Obviously, it would be better to spend a few thousand dollars more and buy a bit that stays on bottom longer while delivering a reasonable rate of penetration. Again, using a cost/ft calculation will lead to the best decision.

Sibley: Cost/ft is the judging factor for bit selection, or overall expenditure for the operation. Calhoun: It could be any or all of the above, depending upon what are the key drivers. It can be kind of a risk-based decision, especially when you start talking about hole quality. If that is really critical – to get a good drillstem test, or get casing to the bottom, or get completion results you need – then, of course, that will be more important than rate of penetration or minimum cost/ft of drilling. That is because you’ll recoup your value in the performance of the well after it’s completed. Hudspeth: Not always (worth the cost). Our judgment is just through experience in a known area. We have run bits, what you would call premium bits, where we might have diamond coatings or impregs on the side for wear. In some cases, as far as the abrasiveness or hardness of the formation is concerned, sometimes premium bits don’t warrant the use. Q. Does this judgment change with locations, as in one example, for an expensive well?Sarrafian: Absolutely. However, the bit selection is still based on cost/ft and a desire to drill the quickest well. Sibley: It can. If you look at a cost/ft equation for a bit, a bit cost can be a very small factor when you’ve got a high-dollar operation. Calhoun: Yeah, for sure. Cost of operation always has a big influence on the decisions that we make. You just can’t get away from it. Hudspeth: If you’re going to compare an offshore well to a shallow, onshore hole, then yes, of course this changes. If, for example, you’re going to go to a high-dollar, PDC bit, you’re going to run a new bit offshore, while onshore you’d probably go to something that you ran already. Generally, if it is something that we know has proven itself on performance, whether it is a high-dollar bit or low-dollar bit, we’d rather go ahead and get that performance out of the bit. Q. What hole conditions would justify cheaper bits? Are there any conditions where it is ok to "scrimp" on bit costs?Sarrafian: The bit cost is relatively small when considering the total cost of operations. Therefore, the desire is to get the job done safely and quickly with the right equipment. Sibley: Yes, sometimes you don’t need much of anything from a run. You’re often running a bit for conditioning trips or to finalize a hole section where high dollar bits will not be economical to run. . . . There are operational conditions as such, where there should definitely be cheaper bits on the market. Calhoun: Well, the only good reason should be when that’s how to achieve low well costs or maximum total return on investment.

Hudspeth: Surface holes, soft non-abrasive formations (would justify cheaper bits). In my case, no, I would not scrimp. I guess that if you’re trying to make a project work, and you’ve got an area that’s not that difficult to drill, then yes, you go ahead with the cheaper bit. If you go up to some of these development areas, where we have some coalbed methane, we would go ahead and use something that’s less expensive. Because once you get to the softer formations, all of the bits are about the same. So, the cost might be less by going with a less-known vendor than a "name." Q. Does a deep hole generally call for more expensive bits? Is performance there worth the money?Sarrafian: No, it depends on where the deep hole is located. Generally speaking, the bit is selected on the basis of the types of formations that have to be drilled. Sibley: Yes. Just because of all the things that I said before. To me, everything comes back to that cost/ft situation; in deeper holes, you’re getting into more trip time, and typically you’re getting into harder formations, which may dictate more costly designs. For instance, deep wells take longer to trip, which swings the economics toward staying on bottom. Long trips also factor down the impact of bit cost on overall economics. Calhoun: Yes, when drilling a deep hole or a more expensive well, it is a lot easier to justify the cost (i.e. investment). Time is money on these projects, so you want to keep the number of trips to a minimum, to save money. Premium bits will help you drill more with fewer trips, and thus pay for themselves on such wells. One comment – there is sometimes an irrational preference for longer bit runs with a lower ROP that actually results in higher well costs than more bit runs with a higher ROP. Performance prediction, and confidence in those predictions, is the key, I think, to breaking this trend. As regards performance being worth the money, it should be, if it reduces your total well cost or improves your return on investment (with risk factored in). Hudspeth: No, not always. The reason is that usually in a deep hole – say that you’re going with a roller cone bit – it will be more expensive overall due to the quantity of bits used. Just because one runs a "premium bit" with outside gauge protection, dual seals, etc., doesn’t mean the bit will drill any faster than what is in the hole. So all in all, you’ll end up pulling it, whether it’s a high-grade bit or a medium-grade bit. As to whether the performance is worth the money, well, in a lot of cases, it depends on whether you’re in an abrasive formation, or a normal-pressured formation where the rock strength isn’t that great. Overall, I’d say not always. Q. Does the present market offer bit styles and grades to meet your drilling requirements and bit performance criteria?Sarrafian: Yes it provides us what we need today, but I always want something better. To answer the question – "are we totally satisfied?" – no, we’re never totally satisfied. We would like to drill 1,000 ft/hr instead of 100 ft/hr. I always think that there is room for much more advanced technology. For example, if we could ever develop a way to drill with lasers in our industry, it would revolutionize the drilling business. Sibley: Yes. I think the technology’s pretty good right now.

Calhoun: Yes, but let me qualify that by adding, with emphasis, "within the limits of today’s technology." There are certainly ample choices out there in the field – plenty of suppliers with wide ranges of bit products. Of course, we will probably never have what we really want, which is the ultimate scenario. That would be the ability to drill an entire column from start to finish with a single bit and at the technical limit of hole cleaning, ECD, etc., not the bit limit! Hudspeth: Yes, it does. The main thing that is changing now is the PDC market and the impreg market. For what we’ve got right now, it seems to meet our needs. The only thing that’s not meeting our needs now is an effort to get us something that will last in the hole when the formation’s really abrasive. But that will come along with technology, as it progresses. Q. How would you improve selection, service and performance of suppliers?Sarrafian: With more informed and technically competent service personnel willing to study additional, available data, such as core information, rock mechanics, etc. Sibley: I think that the status of the industry right now is basically that there’s a strong shortcoming of experience, and a lot of people are becoming stretched in their duties. This goes for all entities of the industry, from operators to services, right down to roughnecks. Every drilling rig that can function is presently drilling, and I think that we’re spread too thin, but I don’t know that this can be addressed overnight. Calhoun: I don’t believe that I have a really strong feeling about that. The suppliers that I have worked with are really doing pretty well, all things considered, for what is asked of them. Everything that I can think of (to change on the supplier side) would probably change their overhead cost structure and thus impact the cost of the product. It’s a tradeoff, obviously, and it’s hard to change that when competition is fierce. Hudspeth: From an operational standpoint, I want all the information I can get when making decisions about how to drill a well. Better and complete information will allow me to design the most cost-effective well possible. Tight holes cause me to make allowances for drilling scenarios that may not happen, but could happen, because I don’t have all the information in a particular area. Corporately, it may be the best decision to keep certain information confidential, but from a driller’s perspective, we would rather share information so we can design the best wells possible and stay out of trouble. Q. Is bit selection and performance a key decision in your drilling programs relative to other well designs and requirements?Sarrafian: Yes, it is one of the key decisions. Obviously, there are other key decisions as well, but bits relate to time, and time means money in our business. Sibley: It can be – it depends on where you’re drilling. A big function of well engineering is your time and cost estimation. If you misapply bits, you miss your time, you miss your costs, and you don’t look good professionally. Some places are forgiving when it comes to bit selection, and others are not. It’s all just a matter of performance – hydraulic integrity, mud selection, cement design, operational guidance, all of them are important. Bit selection can be too. It can make or break you in some areas. So, yes and no – some areas are very forgiving, and it’s just rock bits, and in some, you need to do research and use a variety of bits to be successful. It can make a big difference. Calhoun: Not really. Well, let me qualify that. Bits represent a small portion of the overall cost of a well. Yes, they can have significant impact on the total well cost. The problem is that we have many other things to worry about that may be more critical than improving bit performance. Bit performance can get a focus when it’s really bad, of course, or when we must improve performance to make wells economic. We don’t necessarily like it this way, and we know that we sometimes leave something on the table. But like everybody else, we have to choose our priorities every day, and often the bit performance issue never makes it to the top of the list. Hudspeth: Yes, it is – that and the casing

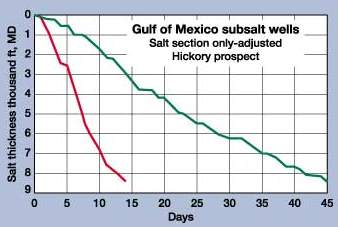

design. This is mainly because, if you can pick a bit to fit the formation, you can minimize on your larger-OD

casing design, casing wear, and increase ROP which minimizes your bottom line. If you’re in something

like a subsalt environment, you’ve got to go to a larger hole casing design which is dependent on what

types of bits are on the market right now.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)